Spotlight Case: Just a Red Eye...Or Is It?

|

|

|

| Sarah Logan, MD | Christina Weng, MD, MBA |

Case History

A 10-year-old Hispanic male presented with a one-week history of intermittent

Color fundus photo of left eye displaying dilated, tortuous retinal vasculature obscuring the optic nerve and macula centrally with slightly dilated vessels along the temporal arcades.

headaches and a two-day history of left eye redness and tearing. He denied blurriness, eye pain, or purulent discharge. On review of systems, he did not have any upper respiratory infection-like symptoms. His past medical history was significant for a large left basal ganglia arteriovenous malformation (Figure 1) causing mild right-sided weakness; prior evaluation by neurosurgeons deemed the malformation inoperable due to its large size and risk of significant morbidity associated with surgery.

Best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/20 in both eyes with no relative afferent pupillary defect. Intraocular pressures were normal OU. Externally, there was no proptosis or lymphadenopathy detected. Anterior segment exam revealed mild, diffuse injection of the conjunctiva in the left eye with a follicular response. Conjunctival telangiectasias were absent. Dilated funduscopic examination of the left eye revealed dilated, tortuous retinal vasculature obscuring the optic nerve and macula centrally with slightly dilated vasculature along the arcades. No vitreous hemorrhage or intraretinal hemorrhages were seen, and the right fundus was normal.

What’s your diagnosis?

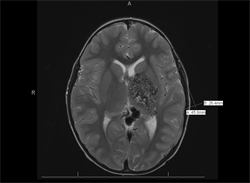

T2-weighted MRI of the brain with contrast displaying large left arteriovenous malformation, centered on the posterior limb of the internal capsule with involvement of the left basal ganglia and thalamus.

Wyburn-Mason syndrome, also referred to as Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome or retinoencephalofacial angiomatosis.

Discussion

The presence of this patient’s retinal and intracranial arteriovenous malformations is consistent with a diagnosis of Wyburn-Mason syndrome. The patient’s left eye injection is probably a red herring and more likely related to a conjunctivitis than venous outflow obstruction or a carotid-cavernous fistula; the latter typically manifests as a sectoral region of injection with individual dilated vessels rather than this patient’s diffuse, mild injection associated with follicles. Additionally, the proptosis frequently seen with a carotid-cavernous fistula is not clinically present here. Neuroimaging of the patient’s brain and orbits revealed normal orbital vasculature.

Wyburn-Mason syndrome is characterized by retinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and is a rare, sporadic condition associated with systemic AVMs that are often intracerebral (midbrain, suprasellar, optic chiasm), mandibular, orbital, or periorbital. It is considered one of the nonhereditary, congenital phakomatoses.[1] The sporadic vascular anomaly usually affects the retina in the posterior pole, but can extend into the temporal macula or peripheral retina.[2] There are three described groups of AVMs; Wyburn-Mason syndrome is most closely associated with Group 3 retinal AVMs. Group 3 AVMs consist of complex arteriovenous communications between large caliber vessels without the interposition of a capillary plexus. This communication allows for direct, high blood flow.3 Fluorescein angiography typically shows a rapid transit of dye through the lesion due to the lack of capillaries; leakage is absent.[3],[4]

Most patients with retinal AVMs experience at least subtle visual symptoms. When there is vision loss, it may be due to a variety of ophthalmic conditions. Reported ocular complications include intraretinal or vitreous hemorrhage[3],[5], exudation and cystoid macular edema[6], retinal vein occlusion[7],[8], mechanical compression of the optic nerve9, retinal detachment[9], rubeosis[10], peripheral retinal neovascularization, and neovascular glaucoma.[11] Unfortunately, retinal AVMs are unlikely to regress spontaneously, but most can be observed conservatively without intervention.[4] Aforementioned complications should be treated accordingly.

When a patient is found to have a retinal AVM, neuroimaging with either magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) of the brain and orbit in addition to magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) should be considered because of the risk of associated systemic AVMs. It is critical to note that some CNS malformations are potentially lethal. Intracranial AVMs can also cause vision loss secondary to stroke or disruption of the anterior visual pathway if the lesions violate the optic tracts or radiations. Neurologic complications include cranial nerve palsies, hemianopia, hemiparesis, and convulsions.[2] AVMs can also cause significant mortality if they lead to intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage.[4] Patients with cerebral AVMs are monitored closely throughout life since cerebral AVMs have the potential to morph over time due to hemodynamic factors, sometimes evolving into spontaneous thrombosis or hemorrhage. Retinal AVMs possess the same potential for spontaneous changes due to turbulent flow and high intravascular pressure which can lead to vessel wall damage and subsequent thrombosis and occlusion.[8] Both retinal and intracerebral AVMs carry low risk for neoplastic transformation.[12]

Take-home points

- Wyburn-Mason syndrome is a rare, nonhereditary, congenital phakomatosis characterized by retinal arteriovenous malformations and often associated with systemic AVMs.

- Reported ocular complications of retinal AVMs include intraretinal or vitreous hemorrhage, exudation and cystoid macular edema, retinal vein occlusion, mechanical compression of the optic nerve, retinal detachment, rubeosis, peripheral retinal neovascularization, and neovascular glaucoma.

- If a patient is discovered to have a retinal AVM, neuroimaging with MRI/CT of the brain and orbit along with MRA should be considered because potentially lethal CNS malformations may be present.

References:

- Wyburn-Mason R. Arteriovenous aneurysm of mid-brain and retina, facial naevi, and mental changes. Brain. 1943;66:163-203.

- Dayani PN, Sadun AA. A case report of Wyburn-Mason syndrome and review of the literature. Neuroradiology. 2007; 49(5):445-456. Epub 2007 Jan 18.

- Archer DB, Deutman A, Ernest JT, Krill AE. Arteriovenous communications of the retina. Am J Ophthaly. 1973;75(2):224–241.

- Schmidt D, Pache M, Schumacher M. The congenital unilateral retinocephalic vascular malformation syndrome (Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome or Wyburn-Mason syndrome): review of the literature. Surv Ophthal. 2008;53(3):227–249. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.10.001.

- Mansour AM, Wells CG, Jampol LM, Kalina RE. Ocular complications of arteriovenous communications of the retina. ArchOphthalmol. 1989;107(2):232–236.

- Onder HI, Alisan S, Tunc M. Serous retinal detachment and cystoid macular edema in a patient with Wyburn-Mason syndrome. Semin Ophthalmol. 2015;30(2):154-156. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2013.835832. Epub 2013 Oct 30.

- Shah GK, Shields JA, Lanning RC. Branch retinal vein obstruction secondary to retinal arteriovenous communication. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126(3):446-448.

- Schatz H, Chang LF, Ober RR, et al. Central retinal vein occlusion associated with retinal arteriovenous malformation. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(1):24-30.

- Medina FM, Maia OO Jr, Takahashi WY. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in Wyburn-Mason syndrome: case report. Arqs Bras de Oftal. 2010;73(1):88-91.

- Bloom PA, Laidlaw A, Easty DL. Spontaneous development of retinal ischaemia and rubeosis in eyes with retinal racemose angioma. Br J Ophthalmoly. 1993;77(2):124–125.

- Rao P, Thomas BJ, Yonekawa Y, et al. Peripheral Retinal Ischemia, Neovascularization, and Choroidal Infarction in Wyburn-Mason Syndrome. JAMA Ophthal. 2015;133(7):852-854. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0716.

- Augsburger JJ, Goldberg RE, Shields JA, et al. Changing appearance of retinal arteriovenous malformation. Albrecht VonGraefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmoly. 1980;215(1):65-70.

Financial Disclosures:

Dr. Logan: None

Dr. Weng: Allergan (C)