Choroidal Nevus

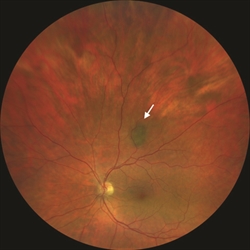

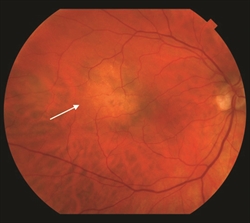

A choroidal nevus (plural: nevi) is typically a darkly pigmented lesion found in the back of the eye. It is similar to a freckle or mole found on the skin and arises from the pigment-containing cells in the choroid, the layer of the eye just under the white outer wall (sclera). (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. A small flat choroidal nevus (arrow). |

Figure 2. Another small benign-appearing choroidal nevus (arrow). |

Some nevi can have areas that appear nonpigmented or amelanotic, and others are mostly amelanotic and appear yellowish rather than brown (Figure 3). Nevi can also develop overlying deposits known as drusen, as well as degenerative changes of the overlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) seen as mottled pigmentation or fibrosis (Figure 4).

Figure 3. An “amelanotic” choroidal nevus (arrow). |

Figure 4. A slightly raised choroidal nevus with drusen (yellow dots) on surface. |

The estimated prevalence of choroidal nevi in the United States has been reported to be 5% with significant variation by race: 5.6% in White individuals, 2.7% in Hispanic populations, 0.6% in Black individuals. The estimated prevalence of choroidal nevi in Asian populations has been reported at 1.8% to 2.9%.

Symptoms

Most commonly, a choroidal nevus does not cause any symptoms and is found on routine eye exam. However, sometimes nevi under the center of the retina (the macula) can cause blurred vision. When a nevus causes degeneration or dysfunction of the overlying RPE, fluid may accumulate under the retina or abnormal blood vessels (choroidal neovascularization) may develop and bleed or leak fluid.

Diagnostic testing

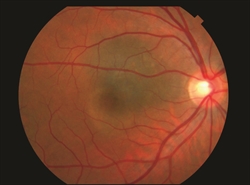

Many nevi can be identified by their appearance alone on examination of the retina. This includes a brown to slate gray coloration with distinct but mildly blurred margins where the color of the nevus blends into the normal retina.

Most nevi are flat or have minimal elevation of 2 millimeters or less. Some eyes have more than one nevus, and nevi may also be found in the fellow eye. Retinal photographs of the nevus are typically performed to allow them to be monitored for any signs of growth on subsequent office visits.

Additional diagnostic testing of larger or suspicious nevi includes optical coherence tomography (OCT), ultrasound to measure the size and thickness of elevated nevi, and fluorescein angiography. Less frequently, imaging techniques including indocyanine green angiography, optical coherence tomography angiography, and fundus autofluorescence photography are utilized to assist in diagnosis.

Treatment and prognosis

Most choroidal nevi remain benign (non-cancerous) and have no symptoms. However, occasionally, a nevus can transform into uveal melanoma. The rate of choroidal nevi transforming into melanoma is estimated at approximately 1 in 9000 per year. When a nevus shows significant growth over a relatively short period of time (such as 1 year), it is presumed to have become malignant (cancerous).

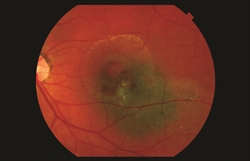

Clinical features of a nevus associated with growth include thickness greater than 2 mm, subretinal fluid, symptoms (such as decreased vision, flashes of light, or floaters), orange pigment, and location close to the optic

disc (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A choroidal nevus associated with a small blister of subretinal fluid. Although presence of subretinal fluid is a risk f actor for growth, this nevus has remained stable without transforming into melanoma. |

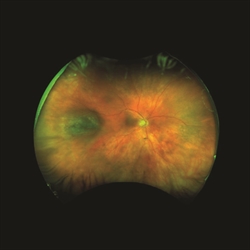

Figure 6. A choroidal nevus with associated fluid and blood due to the development of abnormal vessels under the retina (choroidal neovascularization). This complication can cause vision loss but is not a sign of transformation into melanoma. |

Nevi without any clinical risk features may be examined annually. However, those with one or more risk factors should be examined approximately every 4 to 6 months. Evaluation of these lesions would include a dilated retinal examination and possibly ultrasonography, fundus photography, and OCT.

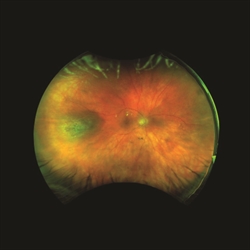

Most nevi do not require any specific treatment. However, choroidal neovascularization associated with nevi can be treated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents (Figure 6). A nevus that has demonstrated growth or has suspicious features should be evaluated by an ocular oncologist (an ophthalmologist specializing in treating eye tumors), and if determined to be a melanoma, would most commonly be treated with radiation (see Intraocular Melanoma Fact Sheet) (Figure 7)

Figure 7. (A) A choroidal nevus with mild elevation. (B) The same lesion showed increase in thickness 2 years later and was diagnosed as a melanoma. |

|