Epiretinal Membranes

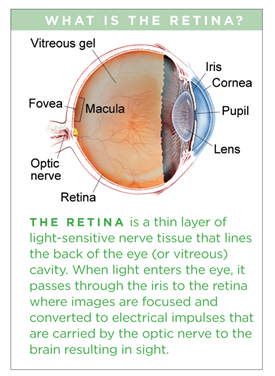

(ERMs), also commonly known as cellophane maculopathy or macular puckers, are avascular (having few or no blood vessels), semitranslucent, fibrocellular membranes that form on the inner surface of the retina. They most commonly cause minimal symptoms and can be simply observed, but in some cases they can result in painless loss of vision and metamorphopsia (visual distortion). Generally, ERMs are most symptomatic when affecting the macula, which is the central portion of the retina that helps us to distinguish fine detail used for reading and recognizing faces.

PDF Fact SheetLarge-Print VersionSpanish Translation Chinese Translation

Symptoms

Most patients with ERMs have no symptoms; their ERMs are found incidentally on dilated retinal exam or on retinal imaging such as with ocular coherence tomography (OCT). In such cases, patients typically have normal or near-normal vision. However, ERMs can slowly progress, leading to a vague visual distortion that can be perceived better by closing the non- or less-affected eye.

Patients may notice metamorphopsia, a symptom that causes visual distortion in which shapes that are normally straight, like window blinds or a door frame, looking “wavy” or “crooked,” especially when compared to the other eye. In advanced cases, this can lead to severely decreased vision. Less commonly, ERMs may also be associated with double vision, light sensitivity or images looking larger or smaller than they actually are.

Causes

The cause of ERMs is due to a defect in the surface layer of the retina where a type of cell, called glial cells, can migrate through and start to grow in a membranous sheet on the retinal surface. This membrane can appear like cellophane and over time may contract and cause traction (or pulling) and puckering of the retina, leading to decreased vision and metamorphopsia.

The most common cause of macular pucker is an age-related condition called posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), where the vitreous gel that fills the eye separates from the retina causing symptoms of floaters and flashes. If there is no specific cause apart from the PVD, the ERM is called idiopathic (of unknown origin).

ERMs can be associated with a number of ocular conditions such as prior retinal tears or detachment, retinal vascular diseases such as diabetic retinopathy or venous occlusive disease; they can also be post-traumatic, occuring following ocular surgery, or be associated with intraocular (inside the eye) inflammation.

Risk factors

The risk of developing an ERM increases with age, and persons with predisposing ocular conditions may develop ERM at an earlier age. The most common association, however, is PVD. Studies have shown that 2% of patients over age 50 and 20% over age 75 have evidence of ERMs, although most do not need treatment. Both sexes are equally affected. In about 10% to 20% of cases, both eyes have ERMs, but they can be of varying degrees of severity.

Diagnostic testing

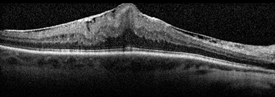

Most ERM cases can be diagnosed by an eye care provider during a routine clinical exam. Ocular Coherence Tomography (OCT) is an important imaging method used to assess the severity of the ERM (Figure 1). Sometimes, additional testing such as fluorescein angiography is used to determine if other underlying retinal problems have caused the ERM.

Figure 1 Epiretinal Membrane (OCT) Image courtesy of John Thompson, MD |

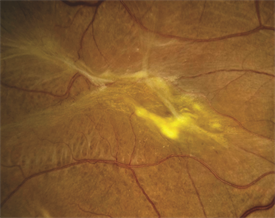

Figure 2. Epiretinal Membrane Sharon Fekrat, MD, FACS, Duke University Eye Center. Retina Image Bank 2012; Image 1437. ©American Society of Retina Specialists |

Treatment and prognosis

Since most ERMs are fairly stable after an initial period of growth, they can simply be monitored as long as they are not affecting vision significantly. In rare circumstances, the membrane will spontaneously release from the retina, relieving the traction and clearing up the vision. However, if an exam shows progression and/or functional worsening in vision, surgical intervention may be recommended.

There are no eye drops, medications or nutritional supplements to treat ERMs. A surgical procedure called vitrectomy is the only option in eyes that require treatment. With vitrectomy, small incisions are placed in the white part of the eye, and the vitreous gel filling the inside of the eye is replaced with saline. This allows access to the surface of the retina where the ERM can be removed with delicate forceps, thereby allowing the macula to relax and become less wrinkled. Visual recovery is slow and most eyes experience improvement within 3 months but it may take a year to attain maximal visual acuity improvement.

The risk of complications with vitrectomy is small, with about 1 in 100 patients developing retinal detachment and 1 in 2000 developing infection after surgery. Patients who still have their natural lens will develop increased progression of a cataract in the surgical eye following surgery.

Factors affecting visual outcome include:

- Length of time the ERM has been present

- The degree of traction (or pulling)

- The cause of the ERM (Idiopathic ERMs have a better prognosis than eyes with prior retinal detachment or retinal vascular diseases

Surgery for ERM has a good success rate, and most patients experience improved visual acuity and decreased metamorphopsia following vitrectomy.